The Company

ALETHEIA – ILLUMINATING WORLDS

THE FIVE LENSES SERIES, VOL. 1: RED ASSOCIATES X PHOTOGRAPHER ALASTAIR PHILIP WIPER

COPYRIGHT RED ASSOCIATES 2019

TEXT

Anna Ebbesen

Ian Dull

Filip Lau

Nanna Sine Munnecke

Ann Marie Healy

PHOTOS

Alastair Philip Wiper

DESIGN

Nanna Sine Munnecke

Arco

Preface

Companies are never frozen in time. They are dynamic, living systems. Given this, the well-oiled machinery of everyday businesses—predicated on rational analysis and management science—is really only useful in the most stable of market conditions. In the midst of turbulence and change, we need to use a different set of tools. At ReD Associates, we specialize in business challenges that involve the highest degrees of uncertainty.

It is convenient to think that big market disruptions are driven by hard factors like the invention of new technologies, corporate strategies, demographic changes or mega trends. But in reality, most of these hard factors are all heavily influenced by softer factors like cultural changes, new social behaviors, or changing patterns in how people adopt and use technologies.

With this book series, we invite you into our workshop to share some of the tools we use to analyze these soft factors. They ultimately lead to the insights that create new, commercially promising and lasting ideas. We call the series Aletheia, ancient Greek for ‘disclosure’. The title refers first and foremost to the kind of disclosure, or new perspective, we strive to obtain when working on a problem where conventional problem solving approaches have proven insufficient.

One such tool for disclosure is called The Five Lenses: A deep dive into five areas that are affecting and shaping the business model, or the source of income in question, for years to come. In our work we have found that forcing yourself to look at a given commercial problem from five very different viewpoints can provide the knowledge needed to illuminate a new and prosperous path forward for a company, a business line, or a troubled product category. The five viewpoints combined will help in forming a new and profound perspective with the potential to change marketplaces.

Using methods and theories from the human sciences, it is possible to put oneself in a position to deliberately learn essential lessons about what it means to be a company––the good and the bad, what impacts the company’s definition of “good” and “bad”, how that mirrors the company’s place in the world, what role it plays in consumers’ lives, where it stands in the industry or the wider society as a whole, and where it is situated when it comes to scientific advancements impacting the entire ecosystem. The Five Lenses framework is essential for structurally taming the new.

THE FIVE LENSES

THE COMPANY / PEOPLE / TECHNOLOGIES / THE INDUSTRY / MARGINAL PRACTICES

This publication is an attempt to unpack one of the lenses: The Company.

The five volumes in this series will not look like the usual business books. Instead, we have chosen to experiment with the format from volume to volume. In this first book, we have collaborated with art photographer Alastair Philip Wiper, who has gone to Indonesia, Germany, France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom to explore how the world looks inside companies, and how consumer products are created. Alongside Wiper’s photos, you will find a number of short essays on five recurrent themes that are essential to grasp when companies want to move towards something new.

Thanks to our friends at adidas, Pernod Ricard, and Kvadrat for opening their doors and allowing us to disclose worlds normally hidden to most of us.

This book contains photographs by Alastair Philip Wiper from the working facilities of three of ReD Associates’ clients: Kvadrat, Pernod, and adidas, in Indonesia, France, U.K., Sweden and Denmark. The images are accompanied by short essays on ReD Associates’ approach to understanding companies on the cusp of major change.

FEATURED IN DOMUS MAGAZINE & DEZEEN

“The aesthetic is the guiding force, turning something that is intended to be purely practical into a thing of beauty. I wanted to be able to show as much as possible in as few images as possible. Not to give a detailed explanation of what happens at a company, but a glimpse of certain aspects, and still leave room for questions, with each image standing on its own.”

– ALASTAIR PHILIP WIPER, 2019

Introduction

WHAT DRIVES COMPANY BEHAVIOR AND DECISION MAKING?

Why do some companies embrace new market or technology opportunities quickly, while others react slowly in risk-averse ways, always a little too late to the latest major shift? How is it that some companies quickly recover after failed attempts at new commercial opportunities, while others are shamefully hiding failures in a closet of taboos?

When trying to understand a company, its culture and strategy, we find that there are five reoccurring themes that are essential to grasp.

ASSETS

Everyone is talking about disruption and digital, but the world is still inherently physical. There is so much hidden in the asset category of balance sheets that modern marketing and buzz about the future leaves out. Machines, factories, and the skill and craft of the people who interact with them are an essential part of a company’s culture, and must be viewed as such.

ORTHODOXIES

Decision making is often predicated on unspoken rules and habits: “how we do things here.” Orthodoxies govern the different ways reality is structured in each and every company––it is all the assumptions a company makes about their customers, consumers and the world that they live in. Bets on new ventures will only be successful when these assumptions are in line with the real world.

EXCELLENCE

True excellence is a goal of all great companies. Here one can see the complex process of marrying standardization with a mastery that comes close to perfection. Every day, on these factory floors, people and machines come together to make products worthy of pride. We can celebrate––not just the design and innovation––but the replicability. Without the ability to produce excellence consistently at scale, no business can ever truly take flight.

MYTHOLOGIES

The way a company tells its own story says a lot about how it sees its role in the larger world––past, present and future. Great companies leverage their founding mythology into a blueprint for future innovation and growth. The more they create a culture around this narrative, the more they implicitly understand how to create value in the marketplace.

VALUE

Without a unique and relevant business model, a company does not have the platform to take risks and explore the innovations that matter most. This kind of model can only happen when we cultivate a perspective--when we interpret which pieces of data and knowledge are the most important and develop a feel for how to go forward with decisions. With a perspective, the company has the courage to move on the most meaningful opportunities.

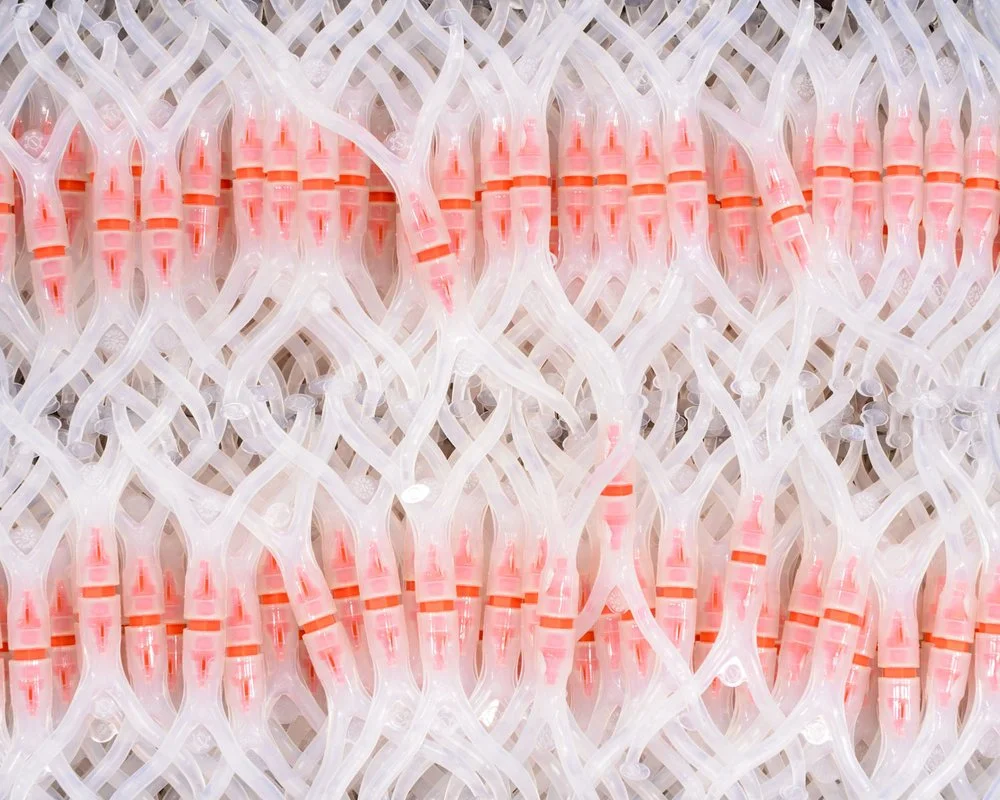

Assets

“Assets” call to mind an annual report or line items on a budget plan. We think of numbers with commas and the conceits of finance. Every good business relies on assets but, in talking about them in such abstract terms, we lose touch with their physicality––machines have girth, grit, mass. Visualizing them and experiencing them makes our understanding of their value quite different.

When we see the faded paper collected in years of customer log books in a production hall or the vibrant colors and patterns in a new season’s pallets stacked together in a textile mill, we come to a fuller understanding of what assets mean to the company. These are not merely numbers but tools, materials, skill, history, care, and craftsmanship. They also remind us why things sometimes take time––be it production or change. When we stand on a factory floor, we intuitively understand how difficult it is to change a production setup much less to completely replace one. If we want to truly understand a company, we need to step away from the Excel spreadsheets and follow Wittgenstein’s advice: “Don’t think, look.”

Material assets also reveal, beyond the numbers and abstractions of finance, what the company itself has found and, perhaps, still finds valuable. In their three-dimensional form, they show us how different companies orient themselves in the world. They are the exact opposite of fungible––they are grounded in time and place. And this very inability to extricate them from their context is the reason we need to make the extra effort to pay attention to them. They reveal the power, beauty and potential the physical continues to hold.

Orthodoxies

For most of us, the definition of what is right and wrong is a given. In the midst of routine practices, our mind relies on a set of assumptions about how the world works that allows us to focus on more demanding cognitive tasks. This default thinking is so familiar to us––the very air we breathe––that we are no longer able to explain it or even to see it. It is what we dare take for granted about the world. These types of assumptions can serve us well on any average Tuesday. But what happens when the outside world begins to change?

Once assumptions are firmly rooted in our cultural understanding, they have a way of becoming ever more entrenched. In fact, we tend to prune our experiences to seek out opinions and facts that support these original beliefs and hypotheses. The filter bubble is a very human creation that technology has only enhanced.

Often, we only see assumptions when the convention is broken: we only realize champagne isn’t served at a funeral when we watch the widower pulling out the cork. When we sense that our assumptions and biases are outdated or even wrong, the instinctive reaction is disbelief followed by further entrenchment––as unhealthy for a human being as it is for a company. When core decisions are based on assumptions that no longer hold, your company will end up making the wrong bets because the world is no longer what you believe it to be.

Maybe your company bets that people play sports to win, or that children want instant traction from their play, or that sweeter drinks always taste better. But what happens when yoga becomes a sport, or when kids put in both time and serious physical effort gaining mastery in a skill, or when the taste of sweetness is not culturally appropriate? In all of these examples, company assumptions keep products from delivering on their promise to consumers. All businesses are bets on human behavior. If you assume the wrong things, you will make the wrong bets.

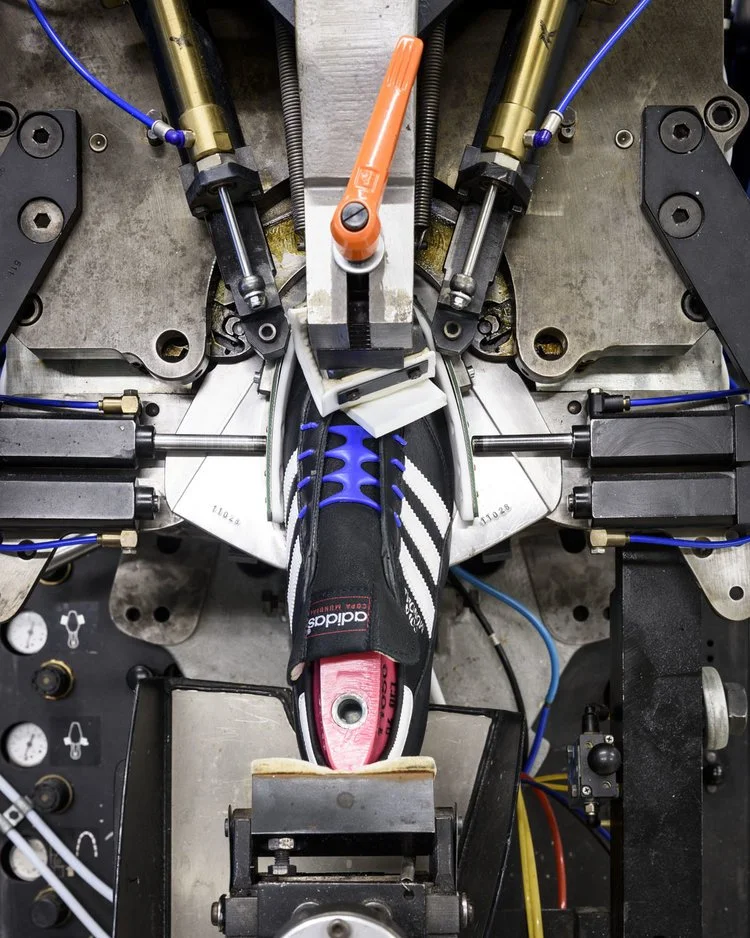

Excellence

What makes something good? When is it better than the rest? Assessing excellence isn’t easy. How do we begin to define the parameters? The weight of a specific material, the durableness, its reception in the marketplace? The answer varies for each and every company, but the goal is always the same: a sense of pride in the work.

This pride comes from developing a perspective on how best to make things. Whether it is shoes, bottles, curtains, or pasta, there are many possible avenues towards excellence. Only a company with a sense of perspective will intuitively understand which one to take.

On the factory floor, for example, choices of materials, textures, tastes and design are realized, and processes are created to ascertain that each and every product achieves seemingly impossible standards. Do the bottles withstand pressure, as they should? Will the liquid have the right color? Do the fabrics continue to match the exact metrics of size and shape with every roll, every cut? All aspects must be tested again and again and again against the very real elements of our physical reality––does each and every shoe stretch, breathe, bounce, dig, drag, grip, and give? Does each and every bottle of vodka look, taste, smell, sound, and feel like the other ones in the box?

Whether it is the exactness of color in a certain thread, the quality of suppleness in the shoe leather, or a curve in a bottle that dips just so, the final result presents us with this window into idealism. After all, there is no such thing as a generic shoe––no one shoe to rule them all. There are only particular instances of shoes. Yet each one seems destined to be the contender in an ongoing quest for perfection ––the one closest to an ideal of the shoe. It is Plato’s notion of ideals merged with human ambition. And it is only because of this human condition that we can obtain mass production at scale, where sameness and uniformity––living up to consumer expectation of repeat experiences––is a virtue fulfilled.

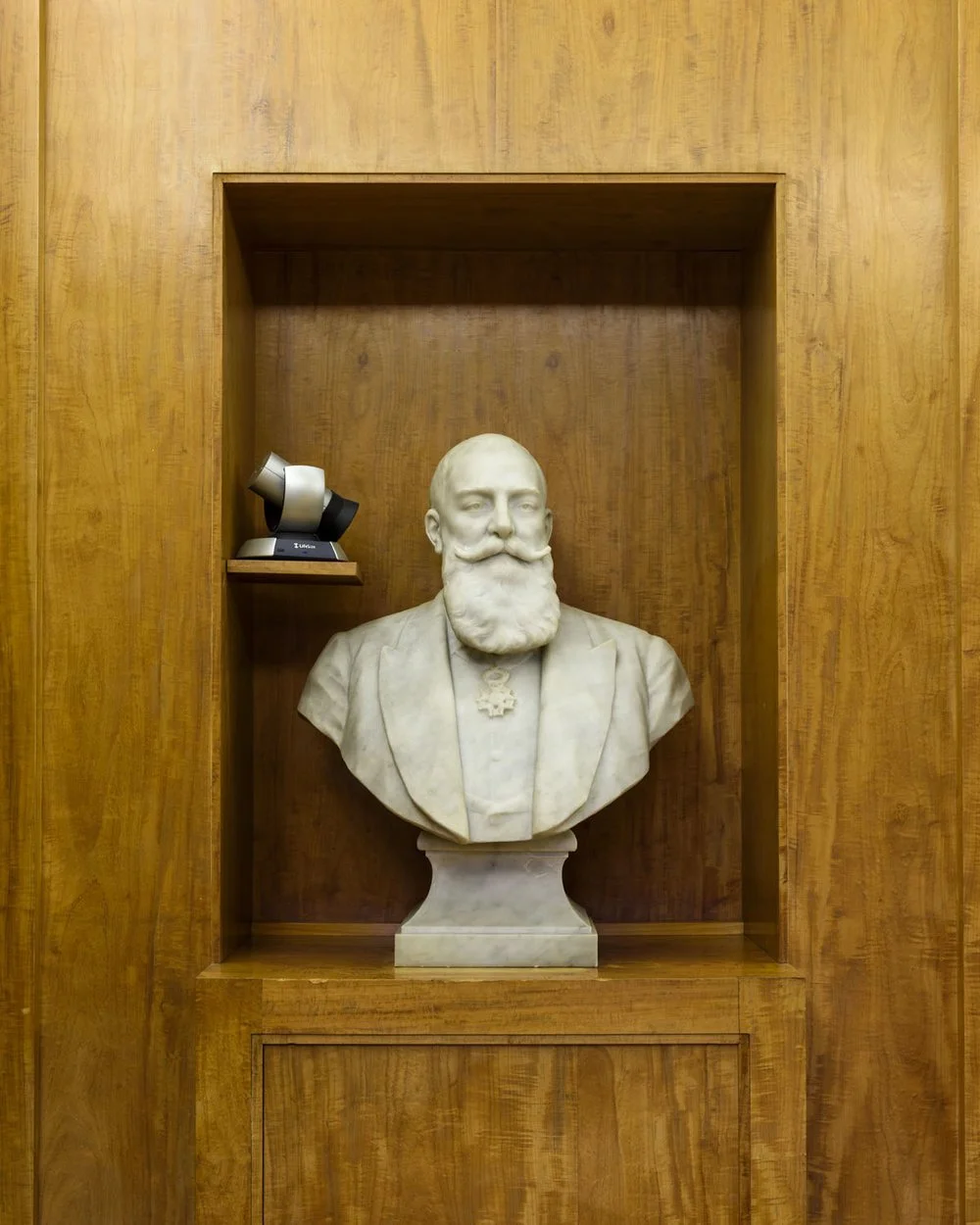

Mythologies

All companies begin with a story. But not all of them leverage that story into something significant, fueling an identity or innovation. The more a company continues to riterate a powerful narrative––its myth of creation, of struggles and of overcoming them––the clearer the path becomes towards growth. We see this when people in adidas constantly find renewed inspiration in statements from the founder, Adi Dassler, or when LEGO goes back to the ‘commandments’ of LEGO Play according to the second generation owner in the sixties.

When a company does not have an implicit understanding of its own myth, when it attempts to define itself solely through lines in a powerpoint, its coherence is left vulnerable to turbulence from the outside world. The company’s culture drifts away from unity into smaller tribal factions. It can never achieve what the Ancient Greeks once called autopoiesis, or a replication of itself. A company might expand but it does not take its DNA along with it. Without an ever evolving myth, we have no core to measure input up against, nothing to help us in selecting what to take in and what to leave out––which trend to bet on, and which one to let pass.

Over the years, many have tried to bring founding myths into the everyday life of the company through explicit references written in the halls, but a company mantra or manifesto will never permeate a culture simply by being articulated and published. Inspiring mythologies are seen in the unspoken sense of involvement and deep interest people take in their work. It is in the way a company can expand from ten to twenty to two hundred to two thousand and still hold tight to its original ethos. A company with a strong mythology has a shared meaning that is palpable to everyone who is a part of it, including its end customer.

Value

When we have a take on a problem or situation, we know how to act on insights and revelations. We can see what connects with what and we intuitively sense which data, input, and knowledge actually matter. Caring is the human superpower that enables us to set a course that is meaningful.

But this kind of care is only possible when a company also has surplus––both financially and mentally. When the business model is the platform––and not the reason for being––it allows us to risk, innovate, and change as well as to celebrate tradition and history. Surplus gives us the freedom to pursue what we care about most, sharpening our profile.

In this care, we understand that there is not one right answer. Discernment is not about paying attention to everything. It is about artfully interpreting some things. In both the sciences and humanist endeavors, there are many ways to arrive at an endpoint. Which one is the most beautiful? The most compelling? The most powerful? The most pleasing? An algorithm can arrive at optimization, but only someone with a sense of perspective can interpret the meaning of the destination. Only then can you grow in a way that is sustainable in both the short and the long run.

With this kind of care, opportunities for growth reveal themselves. And when companies share a perspective, they share a mindset about how to recognize such opportunities. They earn their profits, not by imitating others, but by making themselves matter to the people in their world. They succeed because they actually give a damn.

Great strategy manages to ensure a profit model that consistently delivers. It brings the needed abundance to do things that really matter today and into the future.

Companies

Pernod Ricard

ABSOLUT, ÅHUS, SWEDEN

THUIR, FRANCE

Adidas

HQ, HERZOGENAURACH, GERMANY

SPEEDFACTORY, ANSBACH, GERMANY

SERANG CITY, INDONESIA

Kvadrat

HQ, EBELTOFT, DENMARK

WOOLTEX FACTORY, HUDDERSFIELD, ENGLAND

Alastair Philip Wiper

Alastair Philip Wiper is a British photographer, based in Copenhagen, working worldwide. From the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland to giant shipyards in South Korea and radio observatories in Peru, Alastair Philip Wiper works with the weird and wonderful subjects of industry, science, architecture, and the things that go on behind the scenes. He takes an anthropological approach to the subjects of his photography, seeking out the unintentional beauty in the infrastructure.

If you would like to obtain one of our limited-edition copies of the first book, ‘The Company,’ please contact us.